Just before Christmas, the Attorney-General’s Department announced a consultation about whether access to telecommunications data (metadata) retained under the mandatory data retention scheme should be extended to include civil cases.

The timing of this consultation – it was announced the week before Christmas with an original submission deadline of 13th January (since extended to 27th January) – suggests that the government is consciously seeking to ‘slip this through’ while as few people as possible are paying attention.

Mission creep, or a whole new mission?

We don’t actually know yet what the government is considering, as the information they’ve released so far is very limited, but it’s likely that any initial expansion of access will be for a small set of civil case types. While that may at the time seem relatively reasonable to many people, in isolation, it’s likely that this would be just the first of a number of gradual, incremental extensions of access.

Such incrementalism is one of the main political methods by which privacy-intrusive and often marginally-effective programs end up turning into all-encompassing behemoths over time. The method is well-entrenched and is hostile to open accountability, because at each step everyone is told the change is minor, the difference from yesterday is not much, so there’s nothing to worry about (remember George Brandis telling us ‘it’s just the name and address on the envelope’ in this unforgettable interview?).

In reality, this would represent much more than just an expansion in scope – it would in fact be, as Nick Xenophon said last week, “not so much a case of mission creep as a new mission altogether”.

The ‘boiling frog‘

The boiling frog is an anecdote describing a frog slowly being boiled alive. The premise is that if a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if it is put in cold water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. The story is often used as a metaphor for the inability or unwillingness of people to react to or be aware of threats that arise gradually.

The point being, that if we allow access to the data retention scheme to be expanded, it’s likely that it will continue to be incrementally expanded until access becomes effectively unrestricted. This would represent a serious threat to the right to privacy of all Australians.

Write a submission

If you are concerned about this issue, you should write a submission. You don’t need to be an expert on the issue, nor do you necessarily need to go into a great deal of detail. Even a concise, one to two page submission that sets out your position, ideally with supporting references, will help to establish the strength of opposition to the expansion of access to data.

The basics

- Due date for submissions: 5pm AEDT, Friday 27th January 2017

- Include a cover letter, introducing yourself and specifying whether you wish your submission to be published or not, and if not, whether you wish your name to be withheld.

- Be polite and avoid inflammatory language. A bit of understatement is likely to be more persuasive than hyperbole.

- Provide references and supporting evidence for your claims.

- When complete, email your submission to CommunicationsSecurity@ag.gov.au

First, you should review the Consultation Paper. The primary points to note are:

- From 13th April 2017, there is a prohibition on the use in civil cases of any data collected only due to the requirements of the mandatory data retention scheme. This is the date by which ISPs and telcos are required to have systems in place to comply with the requirements of the scheme.

- The government is considering whether there should be any exemptions to that prohibition.

Any such exemptions would be made ‘by regulation’. This means the Attorney-General will simply sign a document allowing access for certain types of civil cases. Such regulations are however subject to ‘disallowal’ by the Senate, within a defined time period.

It’s of course up to you what to include in your submission. You’ll note that there are three specific questions listed in the Consultation Paper. You’re not however obliged to answer any or all of these, so you can frame your submission however suits you best.

For a good example of a short, concise submission, see Griffith MP Terri Butler’s submission.

What data is included?

Much of the data currently retained by telcos and ISPs is already, and will continue to be, available for civil cases. Different telcos and ISPs have different operational and billing processes and therefore the data they already retain, for ‘operational’ purposes varies significantly, as does the length of time the retain that data. You should therefore be careful not to make assumptions about what data is potentially subject to this inquiry.

The fact that ISPs and telcos will have to, for each and every request they receive, first differentiate between the data they are retaining only under the requirements of the mandatory data retention scheme and the data that they are retaining for operational purposes introduces significant practical challenges. From their perspective therefore, it will be much simpler (and cheaper) to comply with the mandatory data retention scheme if either none, or all data is available for civil cases.

There also continue to be a number of inconsistencies and lack of clarity in the definition of the data that must be retained. As John Stanton, CEO of the industry body Communications Alliance, told the ABC last week:

Given this lack of clarity, the simplest and cheapest approach for the industry will be to ‘over-collect’ data to ensure they are compliant with the law. Of course, once the data exists and is retained, it’s likely to be used.

Main points

Below are the main points we recommend you include, starting with the most important.

1. Potential for adverse impact on the effective operation of the civil justice system

As noted in the Consultation Paper, the primary justification for considering exceptions to the prohibition on using for civil cases data that is retained only due to the requirements of the mandatory data retention scheme, is:

…to mitigate the risk that restricting parties to civil proceedings’ access to such data

could adversely impact the effective operation of the civil justice system, or the rights or

interests of parties to civil proceedings.

As the data in question is data that has not before been retained, it has therefore never before been available to the civil justice system. As such, continuing with the prohibition on using such data for civil cases would simply maintain the status quo, and would therefore, by definition not adversely or otherwise impact the effective operation of the civil justice system, or the rights or interests of parties to civil proceedings.

2. Australian Privacy Principle #3.

Another important points is, that any data that is being retained only due to the requirements of the mandatory data retention scheme is, by definition, in direct contravention of Australian Privacy Principle #3, from the Australian Privacy Act:

“the entity must not collect personal information (other than sensitive information) unless the information is reasonably necessary for one or more of the entity’s functions or activities.”

There are however a number of very broad exemptions from these rules that apply to law enforcement and intelligence agencies, and those exemptions are the basis on which the mandatory data retention scheme has been built.

While those exemptions may be justifiable in relation to law enforcement and intelligence activities, they most certainly are not in relation to civil cases.

It is therefore clear that allowing access to any such retained information for civil cases would represent a serious additional undermining of the privacy rights of all Australians.

For more information on the Australian Privacy Principles, see the OAIC’s Fact Sheet.

3. Mandatory data breach notification legislation

This inquiry was a recommendation (recommendation 23) of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, in its 2014 report into the data retention legislation (available from the APH website.

In that report, the Committee also made the following recommendation:

Recommendation 38: The Committee recommends introduction of a mandatory data breach notification scheme by the end of 2015.

The government committed to introduce such a scheme by the end of 2015, however, and even though legislation to do so has been presented to the parliament on at least three previous occasions, this remains outstanding.

The Privacy Amendment (Notifiable Data Breaches) Bill 2016 that was introduced into the House of Representatives in October 2016 unfortunately involves the introduction of a significant element of discretion about reporting for organisations suffering breaches and is therefore unlikely to be effective in many cases.

We believe the government should remove this discretion and should move to pass this legislation promptly. Whether you believe such a scheme would be effective or not, the failure to progress this legislation is symptomatic of this government’s lack of respect for the privacy rights of Australians.

4. Commitments from the Government

As we noted in the introduction above, the government was very clear at the time about the justifications for the introduction of the mandatory data retention scheme.

Attorney-General George Brandis told the ABC’s Q&A program on 3rd November 2014 that:

the mandatory metadata retention regime applies only to the most serious crime, to terrorism, to international and transnational organised crime, to paedophilia, where the use of metadata has been particularly useful as an investigative tool, only to as a tool, only to crime and only to the highest levels of crime. Breach of copyright is a civil wrong. Civil wrongs have nothing to do with this scheme. [Emphasis added]

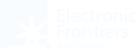

Similarly, the Attorney-General’s Department published the answers to a series of Frequently Asked Questions on its website, which included the following:

Will data retention be used for copyright enforcement?

The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 only allows access for limited purposes, such as criminal law enforcement matters. Breach of copyright is generally a civil law wrong. The Act will preclude access to telecommunications data retained solely for the purpose of complying with the mandatory data retention scheme for the purposes of civil litigation.

Interestingly, this section has now been removed from the page.

Compare the current version of the page with the version from 28th April 2016:

We’re not sure whether the removal of this section is significant or not, but the Department has confirmed to us that it was removed in December, which seems awfully convenient.

As we’ve said in the past, the mandatory data retention scheme is potentially the best thing to ever happen to copyright holders that believe suing people is an effective business strategy. As Graham Burke, CEO of Village Roadshow, said this week, they “plan to sue copyright infringers.”

Allowing access to the full two years of retained data, particularly source IP addresses, for the purposes of copyright enforcement, will likely be of benefit only to the legal profession.

The evidence is in, and the solution to online copyright infringement is simple. As the Productivity Commission states in its recent report into Australia’s Intellectual Property Arrangements, published in December 2016:

There is simply no justification for allowing access to retained telecommunications data for the purposes of copyright infringement.

5. A Privacy Tort

Rather than seeking to further undermine the privacy of Australians by expanding access to retained telecommunications data, we believe the government should be increasing the privacy protections available to Australians.

Australia remains one of the only advanced countries without a right to sue for breach of privacy, and while there have been numerous calls for such a right to be introduced, the federal government is yet to show any interest in doing so. As far back as 2008, the Australian Law Reform Commission first recommended such a right be introduced, and then in 2014, they released a report outlining how such a ‘Privacy Tort’ could be implemented at the federal level, to give individuals the ability to seek redress when their privacy has been invaded.

There is however significant support for a privacy tort at the state level. Last month, the NSW Attorney-General, Gabrielle Upton called for national action on a privacy tort, and is leading a working group to progress the issue. The benefits of having nationally-consistent legislation in this context are self-evident so the federal government really needs to start moving on this issue.

Specific questions in the Consultation Paper

Below are the specific questions set out in the Consultation Paper with our suggestions on how (or not) to respond:

In what circumstances do parties to civil proceedings currently request access to

telecommunications data in the data set outlined in section 187AA of the TIA Act

(refer to Attachment A)?

– unless you have specific relevant experience, we suggest not providing an answer to this question.

What, if any, impact would there be on civil proceedings if parties were unable to

access the telecommunications data set as outlined in section 187AA of the TIA Act?

– unless you have specific relevant experience, we suggest not providing an answer to this question.

Are there particular kinds of civil proceedings or circumstances in which the

prohibition in section 280(1B) of the Telecommunications Act 1997 should not apply?

– answer: no.

Recommendations

Here are some suggested recommendations you may wish to include in your submission:

- There should be no expansion of access to retained telecommunications data for any civil proceedings.

- The government should instigate an urgent review into the efficacy of the Mandatory Data Retention Scheme during 2017.

- The government should ensure that a comprehensive and adequate data breach notification scheme is introduced without further delay

- The government should instigate a parliamentary committee to consider the introduction of a statutory cause of action for serious invasions of privacy (a ‘privacy tort’) as a matter of urgency.

Sign our petition!

We’ve launched a new petition opposing the expansion of access to telecommunications data for civil cases and calling for the introduction of greater safeguards.

Sign our petition now

Contact your MP/Senators

You may also wish to contact your local MP and the Senators for your state about this issue. For guidance on how best to do that, please see our Lobbying Politicians page

Write to your local newspaper

Letters to the editor can be an effective way to highlight an issue. See the contact section on your chosen media outlet. Keep it short and to the point.

Support our work

Feedback

If you have any suggestions, corrections or other feedback in relation to this page, please email us at: policy[AT]efa.org.au.